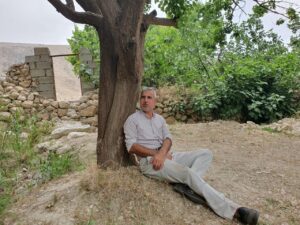

Abdullah Shrem

Credentials

Humanitarian Cause

Emergency Response, Ending Human Trafficking, Violence and Abuse Prevention, Search and Rescue Operation, Humanitarian Negotiations, Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

Impact Location

Iraq

Occupation

Mediator / Former Businessman Negotiating the Release of Hostages with ISIS

Photo Gallery

About Abdullah Shrem

Former businessman Abdullah Shrem, also known as “The Beekeeper of Sinjar,” has been helping to free the Yazidis captured by ISIS forces. He and his aides have rescued almost 400 of the thousands of people sold as slaves.

Abdullah Shrem, a Yazidi from Iraqi Kurdistan, is a remarkable humanitarian known for bringing home hundreds of Yazidi women, men and children who were kidnapped and held captive by ISIS. Originally a beekeeper, Shrem sold honey across Iraq and Syria. However, after his sister and niece were abducted, he dedicated himself to saving them and others who had been trafficked by ISIS.

In August 2014, when ISIS invaded Sinjar in Northern Iraq and other forces withdrew, the Yazidis, an ancient religious minority, were left to fend for themselves. Thousands of people were slaughtered in what the United Nations has declared a genocide, while the survivors—predominantly women and children—were kidnapped to later be subjected to sexual slavery or kept as servants.

Later that year, Shrem successfully rescued his first person—one of his nieces. Word of his success quickly spread, and soon local people began turning to him for help.

“I didn’t think for a moment that I could be involved in the rescue field, to save someone. I never had a plan to rescue people, but it was the human thing to do, and God helped me.”

To meet this growing demand, Shrem developed a sophisticated and far-reaching network by utilizing cigarette smugglers and unofficial informants to aid in the rescue of captive Yazidi women and children. Over time, this grew into a highly organized underground operation that functioned not unlike an intelligence agency, planning and carrying out missions with precision.

Many of the rescued women were initially held in Raqqa, a former ISIS stronghold in Syria. To infiltrate the area, Shrem rented a bakery in the city, transforming its delivery workers into informants who collected vital information under the guise of distributing bread across different neighborhoods.

In addition to this, Shrem recruited a woman selling children’s clothing door to door. Her access to households allowed her to discreetly assess who was being held as a servant or slave, an essential role that her ability to enter homes made possible. Despite the perception that only men could carry out such operations, her contributions were pivotal to the success of the rescues. Some operations stretched over months, as the clothing seller had to avoid visiting the same households too frequently to avoid suspicion.

To organize extractions, Shrem used a simple notebook where he would draw up plans and sketches. One victim, for example, was rescued from a cemetery, where she was instructed to go by a contact. One of his most difficult missions involved rescuing four deaf and mute women. To communicate with them, he recorded their families signing messages and instructions for them on video. These videos were then smuggled to the women through his trusted informant, the clothing seller. Against all odds, the plan worked, and each of the women successfully made it back to Iraq.One rescue stands out: a young deaf woman, silenced by trauma, who miraculously found her voice again upon returning home. Her first trembling words were ones of profound gratitude to Shrem, the man who had brought her back from the abyss of captivity.

Shrem and his team cleverly exploited ISIS’s own rigid extremism to aid their operations. For example, because ISIS required women to cover their faces, Shrem’s group would create false IDs for younger women, altering their ages to appear much older, knowing ISIS would never uncover their faces to check for discrepancies.

According to various reports, ISIS captured around 6,000 women and children, subjecting them to sexual slavery and trafficking, while boys were forced into militant training. Despite significant rescue efforts, thousands remain missing to this day. When asked about the situation in Iraq, Abdullah Shrem told Amnesty International: “Islamic State is gone, but we still have so many people in captivity. We feel totally ignored by the international community.”

Shrem has highlighted on numerous occasions that one of the most significant challenges in rescuing missing Yazidi women has been the lack of funds to pay ransoms and smugglers. Initially, most of the money was sourced through private donations, allowing for the funding of critical rescue missions. However, these financial resources have since been exhausted, making the rescue efforts increasingly difficult. Many victims were taken to Turkey and Syria after ISIS’s retreat, but the lack of logistical backing from authorities poses significant challenges when it comes to coordinating rescue operations across borders.

Out of the 56 members of his own extended family Shrem has tirelessly worked to find and bring home, 14 remain missing. Tragically, some of those involved in the search efforts behind enemy lines lost their lives in the process. Among them was the woman who sold baby clothes as part of the smuggling network—she was discovered by ISIS and subsequently executed for her role in aiding the rescues.

Shrem’s heroism extends beyond his rescues. As a vocal advocate for the Yazidi community, he has brought their struggles to the international stage, earning widespread recognition for his relentless pursuit of justice.

The information on this page was last updated on 09/30/2024 and was provided by the Luminary.