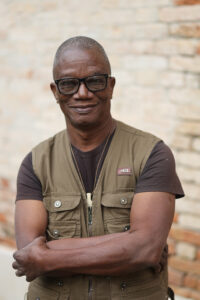

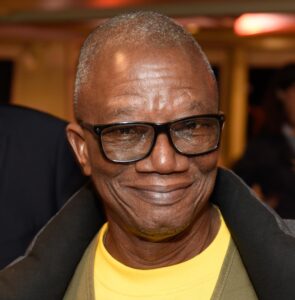

The Breaker of Chains

By Tigrane Yegavian

Grégoire Ahongbonon is the founder of the St Camille Association, which helps people in West Africa suffering from mental illness and seeks to end the inhumane local practice of keeping them in chains. A former mechanic turned mental healthcare activist, he has saved tens of thousands of people from suffering and even death, creating a community of like-minded individuals committed to paying it forward.

Born in 1952 in a Catholic family of a farmer and a housewife, Grégoire Ahongbonon grew up in the village of Kétouké, Benin. At 19, he moved to the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire to stay with a friend of his father’s in the small town of Toumodi, near Yamoussoukro, the country’s capital. He completed his training as a mechanic and settled in the local town of Bouaké, where he opened a thriving tire repair shop. Sadly, his good fortune didn’t last long.

The business soon went downhill, and around 1980, Grégoire Ahongbonon faced a period of great difficulty. It was so hard that the father of six children thought of committing suicide: “I had become miserable; I had lost everything in no time … I almost killed myself. I was lucky enough to meet a priest. He was a French missionary who took the time to listen to me and who supported me a lot.”

In 1982, this priest sent him on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. It was a great turning point in his life, and Grégoire returned a deeply transformed man. “During this pilgrimage, I understood that the Church is the business of all Christians, and that it must be built. I asked myself this question: what was my stone to lay in its foundation?”.

“In Africa, patients who cannot afford to pay for their care are left to die. They are totally neglected, and this situation continues today.”

Together with his wife Léontine, Grégoire started leading prayer groups and went to the Bouaké hospital to visit the sick. He discovered totally destitute patients, often abandoned in their rooms. “In Africa, patients who cannot afford to pay for their care are left to die. They are totally neglected, and this situation continues today,” laments Grégoire Ahongbonon. His vocation was found – he would seek God among the poorest.

“I had become a parent to these patients. I washed them, I found food and medicine for them,” explains the activist. He also went to prisons, a place of great suffering, where Grégoire helped set up a dispensary so that the nurses-in-training from the Bouaké Faculty of Medicine could provide assistance to the inmates. As if by a miracle, his business picked up again, and he used the money he earned to support the sick.

In 1990, Grégoire Ahongbonon came across a naked gaunt man in the streets of Bouaké, going through a trash can in hope of finding food. He couldn’t pass him by. “I saw Jesus in this wandering man with a mental illness. In Africa, everyone is afraid of these patients; they are the forgotten of the forgotten, abandoned by all. They are considered to be possessed by the devil. I had also had this prejudice, but I stopped being afraid,” recalls the activist.

In many African countries, people with mental illnesses are often abandoned or kept in chains by their families who cannot afford proper medical care and feel overwhelmed by dealing with the disease. Grégoire Ahongbonon went out to look for these people and discovered “men, women and children who sought to be loved, like everyone else.”

A year later, he created the St Camille Association. With his wife Léontine, he provided food and fresh water to the mentally ill, but there remained a bigger problem of finding a safe shelter for them. In 1993, Grégoire Ahongbonon garnered support from the Minister of Health, who provided the Association with a room of 2,400 m², where the first center for the mentally ill was opened a year later, on July 14, 1994.

Grégoire recalls a mentally ill person chained by his own parents in a remote village. His sister tried to save him, defying the family ban: “It was a terrible sight. This man was in chains, lying on the ground, deprived of food and water. Unfortunately, we were not able to save his life, but he was at least able to die with dignity.”

Since then, the St Camille Association founded by Grégoire Ahongbonon has opened 12 inpatient psychiatric centers, 67 outpatient clinics and 9 rehabilitation centers. Two of the latter ones recently closed because of the war. Today, the Association operates 88 institutions in Benin, Togo and in Côte d’Ivoire that have already treated over 150,000 people, most of whom have returned to their communities and resumed a normal life. Some remained in the centers after recovering, helping the less fortunate by becoming nurses or in other jobs ranging from doorman to manager. This is the innovative approach used by Grégoire Ahongbonon: the vast majority of caregivers and workers in these centers are themselves former mental patients who have recovered and are often still on medication. For him, helping others is the best way to thank them for the help one has received.

Like the Co-Founders of the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative, he has discovered the source of inspiration that is Gratitude in Action. “This message that the Armenians of Aurora are sending to us is perfectly in line with what we are going through at the moment,” he says enthusiastically. “We must support our brothers whether they are Christians or not, for God does not make any difference between us. We must free them from their chains to rescue them.

In 2024, Grégoire and his team inaugurated a brand-new treatment center in Dassa, Benin, to care for patients suffering from mental illness and drug addiction. It is the only center in French-speaking West Africa to offer this exclusive service to people suffering from these dual problems.

The information on this page was last updated on 09-08-2024 and was provided by the Luminary.